Why Your RIA Succession Plan Is A Fairytale (And Your Next-Gen Knows It)

Gary built something worth walking away from. Twenty-three years running his independent practice. One hundred million in managed client assets. A team of four, including one advisor whom he personally trained and a CSA who's been with him for 15+ years. Client retention above 97%. Revenue growing at a steady clip, mostly from referrals and market appreciation. The kind of practice that feels like proof you did it right.

Gary spent the last five-plus years grooming his lead advisor, Seth, to take over. Seth knows most of the clients personally. He runs the investment committee. He handles the complex cases. When Gary takes a vacation, nothing breaks. The succession plan, at least on paper, looks textbook.

Then Gary's accountant ran the numbers on what Seth could actually afford to pay.

The spreadsheet said no.

Not because Seth lacks talent. Not because the firm is overvalued. But because the math that worked when Gary started his firm in 2002 has quietly, systematically broken down. And Gary is now facing a choice he never anticipated: sell to an external buyer who can write the check, or accept a fraction of what his firm is worth to keep it in the family.

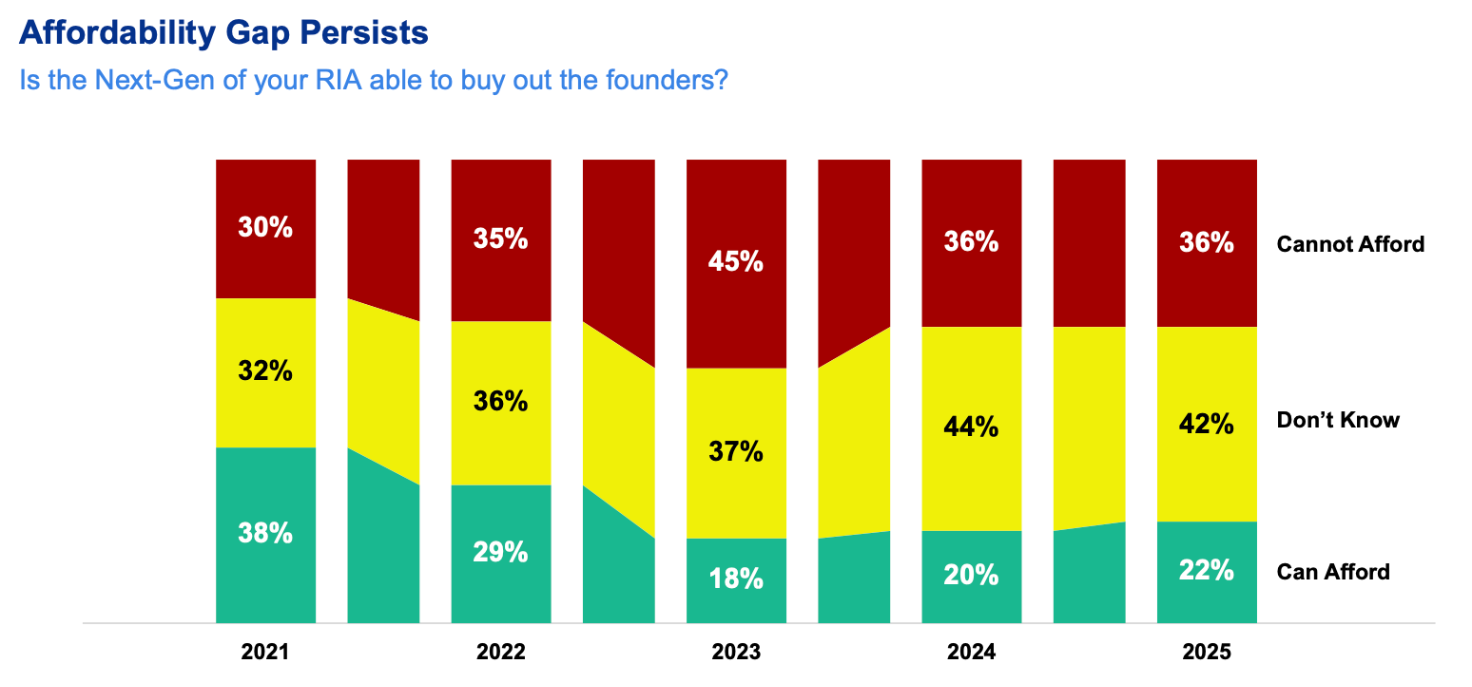

According to DeVoe & Company’s 2025 RIA M&A Outlook, only 22% of RIA leaders say their next generation can afford to buy out the founders today—not in five years after they save more, not with creative deal structuring, but right now. That figure is down sharply from 38% in 2021 and remains far below pre‑2022 levels, even after a modest rebound from the 18% low in 2023.

That means, today, 78% of advisory firms have built succession plans on top of a financial foundation that no longer exists. DeVoe’s Next‑Gen Affordability Index shows that 36% of leaders explicitly say their successors cannot afford to buy them out, and 42% simply do not know, underscoring how few firms have a viable internal path.

The Timing Problem Nobody Talked About

The conventional wisdom around internal succession went something like this:

Mentor your next generation → Gradually hand over client relationships → Structure a buyout over seven to 10 years → Retire knowing the business you built will continue serving the clients you care about.

It sounded reasonable because, for decades, it was reasonable. DeVoe now describes the independent RIA segment as being in a succession crisis, with the traditional internal path slipping out of reach for the majority of SEC‑registered firms.

But three forces collided while advisors were busy serving clients.

First:

RIA valuations climbed far faster than most founders expected. The median valuation multiple for profitable RIAs reached roughly 8–11 times adjusted EBITDA in 2024, up from closer to 5–6 times a decade ago, with higher-performing firms at the top end of that range. Firms that might have sold for two million in 2015 are now commanding six million or more when you combine higher earnings with higher deal multiples. The enterprise value grew faster than anyone's savings rate.

Second:

The window for affordable equity migration kept shrinking. Advisors who intended to start transferring ownership in their late fifties often delayed because the business still felt essential, clients still wanted them specifically, and the financial equation still penciled. By the time they were ready to pull the trigger, the affordability gap had widened into a chasm, a pattern that shows up in industry data as the average owner age approaches the late fifties, with succession actions lagging behind stated intentions.

Third:

Compensation structures never caught up. Most next-generation advisors earn solid livings—comfortable six figures in many cases—but not the kind of wealth that allows them to personally guarantee a multi-million dollar note at 7–11 times EBITDA. Their W‑2 income supports a family and a mortgage; it does not, on its own, support acquiring a business valued at contemporary RIA deal multiples without external financing or seller concessions.

Gary did not make a mistake. He made a series of entirely rational decisions that assumed the future would look like the past. The business and market conditions stayed strong, so he stayed active. Seth earned good money, so Gary assumed he was building the capital to eventually buy in. And the clients loved the continuity, so there was no external pressure to force the issue.

Then the bill came due.

The Institutional Answer: Loans, Haircuts, and Hidden Trade-Offs

Some larger broker-dealers and RIA networks recognized this problem before individual advisors did, and they have started offering financing solutions designed to keep succession internal. On the surface, these programs look like lifelines. An institution provides capital to next-generation advisors, sometimes at below-market rates. The exiting advisor gets liquidity. The successor gets ownership. Everyone stays in the family.

The details, however, tell a more complicated story.

Some networks offer forgivable loans, where a portion of the debt is forgiven if the successor remains with the firm and meets certain production or retention benchmarks over a defined period—typically five to seven years. This makes the deal more affordable for the next generation, but it also locks them into the network. They are not truly independent owners. They are obligated performers.

Other programs involve fee haircuts, where the exiting advisor agrees to a below-market valuation or deferred payments in exchange for keeping the business internal, effectively accepting a discount relative to open-market valuations to facilitate continuity. The successor benefits from a lower purchase price, but the founding advisor takes a significant financial hit. What was worth six million at market can quickly become four million or less in an internal transfer when discounts and structural concessions are layered in.

And in nearly all cases, these institutional financing programs come with strings: continued affiliation with the broker-dealer or network, restrictions on future M&A activity, and oversight on how the business operates post-transition. The succession happens, but independence erodes.

Some exiting advisors have tried to thread the needle themselves. They structure seller-financed notes with extended terms, betting that their successor can grow the business enough over ten years to afford the payments. Others blend internal and external capital, selling a minority stake to a strategic buyer or private equity partner while giving next-generation advisors a smaller ownership slice they can afford. These approaches can work, but they require sophisticated deal structuring, aligned incentives, and a level of financial and operational transparency that many founder-led firms simply do not have.

The uncomfortable truth is that most advisors approaching retirement want two things that increasingly cannot coexist: maximum valuation and internal succession. The math only works if one gives.

What Buyers See That Founders Do Not

When internal succession fails, the natural next step is exploring external M&A, and this is where the consequences of delayed succession planning show up in ways that shock advisors.

Buyers do not just evaluate revenue and client retention. They evaluate cultural fit and organizational readiness:

- leadership depth,

- documented processes,

- client relationship mapping, and

- a firm’s ability to operate without the founder.

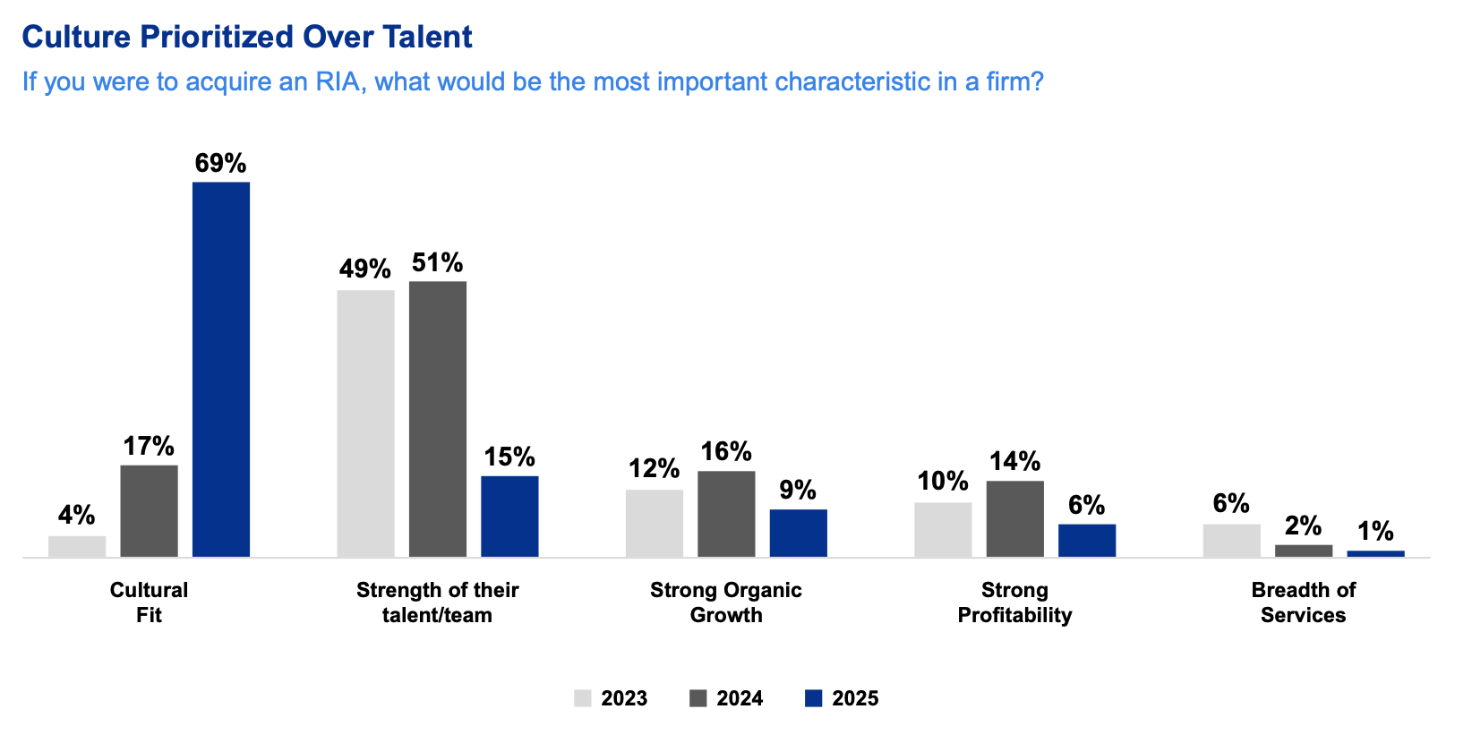

A firm that cannot execute internal succession signals deeper structural problems, such as over-reliance on the founder, unclear leadership, and a culture that has not transitioned from lifestyle practice to scalable enterprise. Per DeVoe's report, cultural fit as an acquisition concern jumped by over by 400% from 2024 to 2025.

These concerns directly affect the three things every advisor cares about during a transaction.

Trust erodes when clients sense uncertainty about the future. If next-generation advisors are not ready or able to take over, clients wonder why. And if the founder has not openly communicated a plan, clients start asking questions—or worse, they start calling competitors. Buyers see this risk and adjust their offer accordingly through lower upfront multiples or heavier reliance on contingent consideration.

Growth stalls when firms stay stuck in founder mode. If Seth cannot step into leadership because the business is still orbiting Gary, the firm cannot invest aggressively in marketing, technology, or new advisor talent. It remains subscale and operationally dependent. Buyers either pass entirely or structure deals with significant earnouts tied to post-close performance, which transfers risk back to the seller.

Valuation suffers because uncertainty is expensive. Firms with clear, executable succession plans and institutionalized leadership tend to command premium multiples—often 10–20% higher—while founder-centric firms with transition risk see discounts in that same range. The difference can easily be 20% or more of enterprise value—not because the business is weaker today, but because the transition is riskier.

Gary thought his succession plan was a people issue. It turned out to be a systems issue. And by the time he realized it, the market had already priced in the risk.

What the 22% Got Right

The firms that can successfully execute internal succession didn't get lucky. They acted earlier, structured ownership migration more aggressively, and treated succession as a multi-year operational priority rather than a single transaction at the end.

- They brought next-generation advisors into equity ownership in their early 40s (sometimes earlier), not in their 50s, matching what many benchmarking studies now recommend as best practice.

- They structured sweat equity provisions and performance-based grants that allowed junior partners to build meaningful ownership stakes before the buyout conversation even started.

- They normalized partial buyouts and phased transitions, so the financial burden was distributed over a longer timeline while the exiting advisor was still actively working.

Most importantly, they stopped treating valuation as a single static number. They recognized that the value they could extract from an internal sale was different—and often lower—than what they might receive from an external buyer, especially as private equity-driven multiples climbed. And they made peace with that trade-off consciously, understanding that control, legacy, and client continuity had a price.

The advisors who waited assumed they could have it all. The advisors who succeeded accepted that they had to choose.

The One Number to Start Tracking Now

If you are a founding advisor with next-generation talent in your firm, there is one question that will tell you more about your succession readiness than any org chart or equity agreement.

What percentage of your revenue could be serviced tomorrow by advisors other than you?

Not theoretically. Not if you spent six months transitioning relationships. Tomorrow.

If that number is below 60%, you do not have a succession plan. You have a dependency problem. And every year you delay addressing it, the affordability gap widens and your options narrow.

Start tracking it quarterly. Measure which clients have met with other advisors, who leads planning reviews, whose name appears on service agreements. Make it visible. Make it a performance metric. Because if your next generation cannot run the business without you today, they certainly cannot afford to buy it.

Gary eventually sold to a regional aggregator. Seth stayed on as a minority partner with an earnout tied to retention. The clients stayed. The business survived. But Gary left several hundred thousand dollars on the table, and Seth will spend the next five years working for a board he does not control.

That was not the plan. But it was the only plan the numbers would allow.

Succession does not fail because people are unprepared. It fails because systems are. DeVoe’s latest survey echoes this, finding that only 27% of leaders believe their next‑gen team is ready to lead, even as awareness of the succession issue hits its highest level on record. And by the time most advisors realize the difference, the most valuable years to fix it are already behind them.

Once the internal math stops working, the exit conversation shifts from “who will buy me out?” to “what, exactly, am I putting on the table?” At that point, your biggest lever is not clever deal structuring—it is the quality of the business you hand over: its growth engine, its documentation, its culture, and how clearly all of that shows up to an outside party. That is the space I work in with founders 2–4 years from pursuing transition:

- Building organic growth systems that do not rely on one rainmaker.

- Documenting processes and client experience so the firm can run without you.

- Aligning brand and culture so what you say you are matches what a buyer or successor actually sees.

We do not run deals, structure transactions, or tell you when to sell. We help you make the practice itself stronger, clearer, and easier to trust—so when you do sit down with an M&A advisor or buyer, you are bringing a real, scalable business to the table.

If you are 2–4 years out and want to stress‑test how “exit‑ready” your firm actually is on those fronts, contact us with “exit‑ready” and I will share the short diagnostic I use to evaluate growth systems, documentation, and brand signals before any talk of valuation.